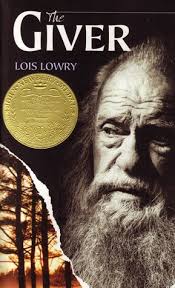

Someday someone is going to have a stack of résumés on a desk. He or she’ll pick up mine early one morning or late one night when he or she really wants to pick up coffee instead. This person will read the frame of my professional life and try to surmise if I’m worth the interview. Let’s say that I am, for the sake of the argument. When I get called into an interview and maybe my hair’s still a little wet from my morning shower and I’m wearing a suit I only pull out a few times a year, I’ll sit in front of this person with my shoulders pushed back—because I’ll have reminded myself that good posture is supposed to be a good sign. This person will ask me what makes me qualified and prepared for the job. My whole body will want my mouth to say, “Guatemala,” hoping that just that word will transfer all my knowledge and experience into this person’s mind The Giver style.

My second urge will be to ask this person to read my personal travel diary even though it’s in Spanish—a next best option for explaining how this summer abroad has changed my life. The truth is, some of the things that give us the best preparation for a path in life, including a career, are often too gigantic to synthesize into a 12-point, Times New Roman, single-spaced blurb. Even if I say this summer has changed my life, I wonder if that’ll mean anything to the person who interviews me. If it didn’t, I wouldn’t blame that person. See, the thing is, when every adult in my life said to me before I left, “You’ll have the time of your life,” it’s not that I didn’t believe them—I just didn’t understand them. How could I? We throw absolutes and hyperboles around so much that we don’t realize how much meaning we strip away every time we use “life-changing” to describe our pizza, a new album, or a newly discovered bookstore. Let me jump off this train back to my point. For half of my life, I’ve wanted to be a teacher and a writer. I’ve made it my ambition in life to work as hard as I can to do both jobs well someday. Three years ago, after tutoring ESL students every day after school for a semester, I knew I wanted to work with English language learners, so I stopped cramming for Spanish vocab quizzes and started asking about the more intricate grammar. Two years ago when I took my first Latin American History course, I also knew that I wanted to write about Guatemala, a country with a history that so painful that it floods the land’s beauty with blood like dye in water. Studying and spending my summer in Guatemala has brought my dreams closer within my reach.

In Guatemala, I’ve learned what it means to be a language learner. My Spanish, although not perfect, has improved faster than a student athlete on steroids. But man, has it been a hard go of it. It’s not just a matter of learning the conjugations, idioms, and sentence structures. It’s not even as simple as using them in regular conversation. It comes down to this: when you’re nervous and flustered at the post office, on a tour, when your schedule changes, or when you’re so lost that you duck into a “Chicken Champion” chain restaurant just to ask directions, can you convey what you mean like a normal human being? Now while I can’t assume the ontological position of (all of the conditions of) an English language learner, I can grasp a heck of a lot better their challenges. I know how scary it is when you don’t have time to strategize sentences strung together in your head. I know what it’s like to struggle with a grammatical structure that absolutely doesn’t exist in your native language. It’s difficult when you concentrate all your energy on just understanding and you have none left over to create a thoughtful response—and I know how it feels when someone mistakes that for disinterest. Worse, I know the sense of helplessness when you realize instantly that you’ve just made a grammatical error and there’s no time for you to let the native speaker you’re with know that you know the correct form without stalling life—but you wish like crazy you could let them know you know.

Living in Guatemala, even for a sneeze-worth of time, has taught me what real poverty and terror can look like for a lot of folks. Frankly, I don’t even like to talk about it too much when my audience can’t see my eyes and know for certain that I’m not bluffing or speaking glibly. Because in addition to these conditions, I’ve seen in Guatemala what it means to enjoy and succeed in life. I’ve seen what it means to have dozens on dozens of different cultures crammed into one environment, and what it actually means to coexist.

At my internship at Los Patojos, an alternative school full of love, creativity, excellence, and bossness, I’ve learned what it means to invest in your students as much as you wish to be invested in, to work long hours, plan lessons and then roll with it when plans change, and to collectively find a great idea and run with it while laughing your eyeballs off. My readings, lectures, and class discussions have taught me the intricacies behind culture and fighting against systemic oppression. In a phrase, from Guatemala I’ve learned how to respect what’s different without making a scene and then to keep working for a better world. All of this and more, I’m sure, will help me as I work as an English or History teacher in a Latino community. Maybe I won’t know a Dominican accent that well, the details of a small regional culture from Ecuador, or the exact chain of events in Mexican history. Still. This trip has made me aware enough to be on the look out so that I can learn.

And as far as writing goes, as kids say these days, the ideas are literally everywhere (no figurative meaning for that “literally”). The mountains look like sleeping dinosaurs covered in moss, the fog floats around the highlands like a sea of clouds, the lakes seem like massive craters in the moon filled with water, and the people have more passion to work for a better Guatemala than any metaphor could explain. The historical, political, sociological, and emotional knowledge I’ve gained has given me what I needed as I write my creative thesis (and hopefully someday novel) about Guatemala—things like jokes, facts so unknown to outsiders that you could never Google them, and belief systems that I’d never learn at my home library in Pennsylvania.

In Guatemala, my life has changed and certainly for the better. I think of my professors and teachers who gave me a boost to where I am now, and I know that whenever I see each of them, I’ll have an uncontainable grin as tell them, “I learned so much,” and I know they’ll understand. I know they’ll grin and nod back at me because more than anything, Guatemala’s taught me how to be a grown-up. More than once I’ve realized that I’m not on some guided tour through life anymore with snacks and hugs provided by adults with nametags—rather I’m on the precipice of having to be an autonomous human being that has to participate in the world without a provided prompt.

A thousand points if you figure out a way to convey that all with sincerity and passion in a 12-point, Times New Roman, single-spaced blurb, because this is one for the books.